Barnamördare. Usurpator. Puckelryggig. Monster. Galen. Många har en bild av Richard III, kanske färgad av William Shakespeares pjäs med hans namn. Eller så är det just att han tog två barn, sina brorsöner, och låste in dem i Towern där han sedan på ett eller annat sätt tog livet av dem man känner till. En medeltida kung med fler historier och skrönor kring sin person än de flesta. Få hade nog kunnat ana att han skulle göra anspråk på 2010-talet.

1924 grundades The Fellowship of the White Boar av S. Saxon Barton, en kirurg från Liverpool, Namnet kom från den vita vildsvinsgalt som utgjorde Richard III:s vapen, och syftet med sällskapet var att rentvå Richards rykte, det om en halt och lytt och nästan vansinnig barnamördare som levt kvar från Shakespeares pjäs. Under 1950-talet ökar intresset, inte minst med utgivningen av Josephine Teys kriminalroman, The Daughter of Time, där Richards skuld i prinsarnas försvinnande granskas och betvivlas. Sir Laurence Olivier släppte en film om Shakespeares pjäs Richard III där det slogs fast att beskrivningen av kungen bara var fiktion och en välvilligt inställd biografi om Richard kom ut. Vinden hade vänt, och 1959 bytte The Fellowship of the White Boar namn till Richard III Society. Fortfarande var det dock ingen som visste var den någorlunda återupprättade monarken hade sin sista viloplats.

Vägen till Bosworth

Richard III var en kontroversiell monark. När hans bror Edward IV dog 1482 utsågs han till förmyndare för sina brorsöner varav den äldsta, Edward var avsedd att bli Edward V. De två pojkarna fördes till Towern för att aldrig någonsin komma ut därifrån, och deras faktiska öden är fortfarande ett mysterium. Kung, det blev Richard själv istället, och även om det vore fel att påstå att han var impopulär hos alla, så fanns det flera tronpretendenter, den främsta av vilka, och den slutgiltiga segraren, var den walesiske adelsmannen Henry Tudor.

Henry Tudor var brorson till kung Henry VI, men hade förlorat sin adliga titel när den sistnämnde störtades och var under många år tvungen att leva i landsflykt. Initialt hade han bara varit intresserad av att få sin titel tillbaka, men med de turbulenta tider som kom med Richards övertagande av tronen från sin brorson så såg han sin chans att få hela kungariket, och lyckades samla en del anhängare.

Det var en vacker dag, den där dagen den 22 augusti 1485. Det var sensommar, och samtida källor nämner att kungen hade solen i ryggen. Hur påverkade Henry Tudors brist på stridsvana hans trupper? Var de nervösa? Kände sig Richard lite mer säker i sadeln, både bildligt och praktiskt talat? Han hade mer erfarenhet av strid än den fem år yngre Henry, och kanske var han helt säker på att han skulle vara den som skulle avgå med segern när de möttes vid Bosworth. Om så var fallet så hade det inte bara med den egna erfarenheten att göra, han gick dessutom i fält med 8 000 män mot Henry Tudors 5000. Bara den numerära övermakten, och obalansen i stridsvana borde ha avgjort det hela. Kanske hade så också blivit fallet om kungen haft en egen armé. Som det nu var, var han beroende av sina adelsmän och deras underlydande som de tog med sig i fält. En av dessa adelsmän var Thomas Stanley, earlen av Derby. Thomas Stanley hade ett rykte om sig att alltid vara på den vinnande sidan, i regel genom beräkning och svek i den sista minuten. Just denna dag fanns det ytterligare en anledning för Richard III att se honom som opålitlig; Thomas Stanley var gift med Henry Tudors mamma, och därmed pretendentens styvfar. För att försäkra sig om att ha Stanley på sin sida hade kungen tagit hans son som gisslan med meddelandet att om Stanley försökte sig på att byta sida på slagfältet så skulle sonen omedelbart avrättas. Thomas Stanley förhöll sig kallsinnig och meddelade kungen att han hade fler söner. Resultatet blev dock att Thomas Stanley till att börja med inte gjorde något. Alls. Bröderna Stanley placerade sig på varsin höjd på vardera sida där slaget skulle stå; the fair green hills of England, så väl omvittnade. Därifrån hade de uppsikt över hur striden böljade fram och tillbaka, som tidvatten. De väntade, in i det sista med att ansluta sig och när det väl skedde, på Henry Tudors sida.

Det sades, även bland hans motståndare, att han kämpade in i det sista men till slut gick det inte mer. ”Galten” blev rakad, sades det

Skelettet framför osteologen Jo Appleby, över 500 år senare, tillhör en vuxen man, i ålder någonstans mellan den sena tjugoårsåldern och den sena trettioårsåldern. Vid närmare analyser, begränsas åldern till att ligga mellan 30 och 34 år. När Richard III dog var han 32 år. Skelettet är finlemmat för en man, men tvärt emot vad Thomas More och William Shakespeare åratal efter den fallne kungens död påstod så finns det inga tecken på vare sig hälta eller en förtvinad arm. Däremot har mannen lidit av en svår skolios som sannolikt skulle ha gjort hans högra axel högre placerad en den vänstra; bakgrunden till den infamösa puckelryggen som fått fäste i Richard III:s eftermäle. Vidare kunde man konstatera att han hade varit cirka 174 centimeter lång, och därmed något längre än genomsnittet av sina samtida. Den sneda ryggen bör dock ha fått honom att verka kortare än han i själva verket var. Skadorna var många, 11 stycken som kunde identifieras på skelettet, och utan tvekan hade de varit ännu fler på kroppens mjukdelar. I samtida källor berättas det om hur ”galtens (en hänvisning till Richards vapen) huvud blivit rakat. Kraniet Jo Appleby hade framför sig hade tre kraftiga skador uppe på skallen, samtliga med tecken på att ha åstadkommits med ett svärd. Högst uppe på skallen fanns ett sticksår. Den kraftigaste skadan påträffades vid skallbasen, en stort hål som bedömdes ha åstadkommits med en hillebard; en spjutyxa, eller liknande. Denna skada hade varit direkt dödande. I ansiktet påträffades flera stickskador, en skada på högra sidans tionde revben och slutligen en huggskada i bäckenbenet som uppkommit efter döden, möjligen ett svärdshugg i skinkan i syfte att förnedra.

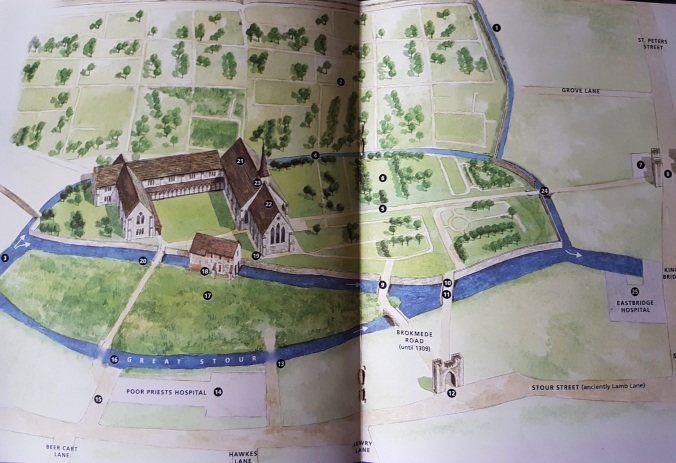

Efter slaget fördes den döde före detta monarken till närbelägna staden Leicester, där han placerades för allmän beskådan i Church of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary för att det skulle stå helt klart för hans anhängare att han verkligen var död. Därifrån togs han till Greyfriars, ett mindre franciskanerkloster etablerat i Leicester 1250.

”Richards kropp hittades bland de övriga döda. Många förolämpningar östes över den, och, inte så humant, lades en snara om hans hals. Han fördes till Leicester. De tog kungen dit den natten, så naken som när han föddes och han lades i Newark där många honom fick se” Crowland Krönikorna, 1486

Grey Friars finns inte längre kvar, inte heller den monument i marmor och alabaster över Richard som hans efterträdare Henry VII enligt samtida källor lät resa tio år efter hans död. Henry VIII:s upplösning av klosterväsendet 1538 hårt åt både ordern och byggnaden, klostret revs, monumentet försvann och genom århundradena skiftade ägarna till den mark som det en gång stod på. 1612 blev det plötsligt en accepterad sanning att den före detta monarken hade grävts upp och hans kvarlevor kastats i vattnet vid Bow Bridge. En plakett sattes upp vid bron, och när man 1862 fiskade upp ett skelett ur dyn så påstods det under en period att den sista Plantagenet-kungen var funnen. Undersökningar av skelettet visade dock så småningom att detta var en annan olycksdrabbad person, och kungen förblev försvunnen.

Arbete för upprättelse

1975 publicerades en artikel, skriven av Audrey Strange, i sällskapets medlemstidning, där hon presenterade hypotesen att kungens kvarlevor fanns under en parkeringsplats i centrala Leicester. Denna hypotes upprepades drygt tio år senare av den engelske historikern David Baldwin som skrev i en artikel att en arkeolog under det tjugoförsta århundradet kanske skulle hitta kvarlevorna av Richard III, och att han själv trodde att de i så fall fortfarande befann sig i Grey Friars-området i Leicester. Genom åren var Richard III Society naturligtvis intresserade av att eventuellt finna var Richard var begravd, men gjorde inga ansträngningar för att starta ett sökande.

Detta kom att förändras. Åren 2004 och 2005 befann sig Philippa Langley, sekreterare för sällskapets skotska gren, i Leicester för att göra efterforskningar inför en dramatiserad, biografisk, film om Richard III. Just under 2005 kom historikern John Ashdown-Hill med ett avslöjande; genom två nu levande ättlingar till Richards syster, Anne of York, hade han säkrat DNA på mödernesidan. Skulle Richards kvarlevor en dag påträffas så skulle det ara möjligt att identifiera honom. Även han hävdade, baserat på sin kunskap om planlösningen för franciskanerkloster, att den forne kungen vilade under en parkering i centrala Leicester, och inte som tidigare misstänkts under bebyggda områden. Under påföljande år finner Philippa Langley funnit en karta som visade var det gamla klostret en gång stått. Det var dags att sätta igång, och projektet ”Looking for Richard” startades.

Sökandet startar

I mars 2011 startades en arkeologisk utredning av Grey Friars för att ta reda på exakt var klostret, och inte minst kyrkans kor hade varit beläget. En undersökning med markradar genomfördes utan att man såg inga tydliga strukturer efter äldre byggnader. Man bestämde sig dock för tre platser för potentiella schakt; en som tillhörde personalen på stadsförvaltningen, en allmän parkering och en närbelägen lekpark. Även i nutid kan myter uppstå, och en av de kring sökandet efter Richard berättar om hur Philippa Langley stod på den första parkeringen, i en ruta markerad med R, vilket för de flesta betyder ”Reserverad” men också kan betyda ”Rex”; kung. Hon skulle senare hävda att hon kände i hela sin kropp att hon stod precis ovanför Richards kvarlevor. Det är svårt att veta vad hon kände och vad som är efterhandskonstruktion; men hon begärde att man skulle gräva just där, och det första av tre schakt öppnades.

Kanske var det tur, eller kanske hade Philippa Langley verkligen känt något när hon stod på den regnfuktiga parkeringen. I detta första schakt påträffades nämligen de skeletterade kvarlevorna av en person. Det är inte svårt att föreställa sig att de närvarande fick gåshud när denna viloplats var helt frilagd. Här låg en person, helt intakt så när som på fötterna, som förmodligen schaktats bort i samband med byggandet av det närmast belägna huset. Graven var för liten för den som placerats där, och från axlarna och uppåt vilade skelettet mot gravens kortsida. Skallen uppvisade omedelbart svåra skador, möjligen från svärdshugg. Det som förmodligen fick tiden att stanna för de närvarande var ryggraden. Vem det än var som låg i graven så hade personen under sin levnad haft en svårartad skolios.

Kroppen tas omsorgsfullt upp och förs till laboratoriet på Leicesters universitet, och det blir nu osteologen Jo Appleby arbete att ta reda på så mycket hon kan om personen man påträffat. Undersökningen av skelettet pågick hela hösten, parallellt med DNA- och benanalys. Den 4 februari 2013 kom så beskedet. Kvarlevorna man påträffat under parkeringens asfalt var bortom all rimlig tvivel de efter Richard III, en gång kung av England.

Kungens ryggrad, och Dominics

När nyheten kom ut i England, att den siste kungen av ätten Plantagenet hade identifierats, satt den då 26 år gamla Dominic Smee och såg detta på TV, och det skulle komma att förändra hans liv. Det var inte bara det att han tillsammans med sin mamma sedan flera år tillbaka årligen deltog i aktiviteterna kring återskapandet av slaget vid Bosworth. Att se Richard III:s kraftigt böjda ryggrad var för Dominic Smee nästan som att se sin egen ryggrad. Både Dominics och Richard har, och hade en mellan 60–70 procentig krökning av ryggraden, och denna typ av skolios är idag ovanlig, då de som har en 50-procentig kurva eller mer i de allra flesta fall genomgår en operation för att räta ut ryggraden. Andra medicinska faktorer hade dock hindrat Dominic från att gå igenom en sådan operation. Nu såg han sin chans att bidra till forskningen kring Richard. När frågorna uppstod om hur Richard verkligen hade klarat på ett slagfält. Kunde han rida och hålla en lans eller kämpa i närstrid med ett svärd, eller var hans eftermäle som skicklig på slagfältet bara ett resultat av medeltida propagandister? Samtida källor berättar hur han ledde anfallet mot Henry Tudors styrkor.

Dominic Smee anmälde sig som stående till förfogande för sådana utforskningar. Därmed började en hård träning både i att slåss med svärd, att rida samt på löpbandet. Dominic kämpade med det senare, då hans skolios påverkade hans bröstkorg och förhindrade att hans lungor att expandera som de behövde. Dominic flämtade och gav sig på nästa utmaning. Att kämpa med svärd, gick det? Det gjorde det, mycket bättre än att springa. Under denna inredning ingick det många ”första gången”, och en av dessa var att ge sig upp på hästryggen, på en häst fysiskt så lik en medeltida stridshäst som möjligt. Man började Dominics lektioner med en med en modern ridsadel, och det gick bra till att börja med, Dominic lärde sig snabbt att rida men han blev också snabbt trött i ryggen. Hur hade det varit för Richard III? Samtida källor, även från hans motståndare, beskrev honom som snabb, skicklig och orädd. Var det inte sant? För även om Dominic Smee klarade av alla de moment som krävdes, så var det fler hinder för honom när det gällde uthållighet och styrka inte minst i rygg och armar. Skulle någon med en närmast identisk kurva på sin ryggrad orka sig igenom ett slag?

Det skulle komma att vända. Den första överraskningen var när man sadlade Dominics häst med den typ av sadel som användes på medeltiden. Tillverkad i trä och hård, men med ett ryggstöd som nådde upp till midjan på ryttaren. Det visade sig att det var exakt vad Dominic behövde för att orka en avsevärt längre stund på hästryggen.

Nästa steg började med en jakt på en medeltida rustning, och då en sådan inte längre finns att uppbringa i England tog jakten forskningsgruppen till Sverige och den danskfödde vapensmeden Per Lillelund, som gör en helt anpassad rustning till Dominic.

Effekten av rustningen är lika häpnadsväckande som den medeltida sadeln, den fungerar som ett stöd för Dominics kropp, kanske liknande det en korsett skulle ha. Den ger ryggraden stöd och gör det lättare att orka. Var det så rustningen också fungerade för Richard III?

Efter att ha låtit Dominic Smee delta i arrangerade strider både till häst och till fots kan det konstateras: med den träning i stridskonst som Richard som adlig fått sedan barndomen så är det högst troligt att han var den skickliga krigare som samtida observatörer hävdat.

Från parkeringen till katedralen

Den 25 mars 2015 var det dags. Trots att drottningen sagt nej till att ge Richard en kunglig begravning skulle han få den närmast statsmannaliknande begravning han hade nekats mer än 500 år tidigare, och det skulle börja där det slutade. Hans kista fördes med bil från det nu uppodlade slagfältet fram till Leicester där kistan lyftes upp på en hästdragen vagn. Omgiven av riddare till häst fördes han högtidligt fram genom Leicesters gator medan en hel värld såg på, 20 000 personer på plats. Ceremonin förrättades av Justin Welby, ärkebiskop av Canterbury, tal hölls och Benedict Cumberbatch, för de flesta känd som Sherlock Holmes i serien med samma namn, men också en avlägsen kusin till monarken dagen var tillägnad, läste den nyskrivna dikten Richard. Richard III hade äntligen förts till sin sista vila.

Källor: https://www.le.ac.uk/richardiii/

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)60804-7/fulltext

Last Days of Richard III – John Ashdown-Hill

King Richard’s Grave in Leicester – David Baldwin